For more than a year, technicians equipped with lasers and radar scanners have been exploring Egypt’s most famous tomb. They’re on a mission to unravel a mystery: Did the mummy of Tutankhamen (too-tong-KAH-mun), also known as King Tut, have company in his tomb?

A prominent archaeologist thinks so. He theorizes that the mummy of another legendary figure, Queen Nefertiti, lies hidden behind one wall of Tut’s final resting place.

The possibility has shaken the world of Egyptology. “It could be the discovery of the century,” said Mamdouh el-Damaty, a former government official in charge of guarding Egypt’s antiquities. Such a find could also provide a much-needed tourism boost to a country plagued by political instability and terrorism in recent years.

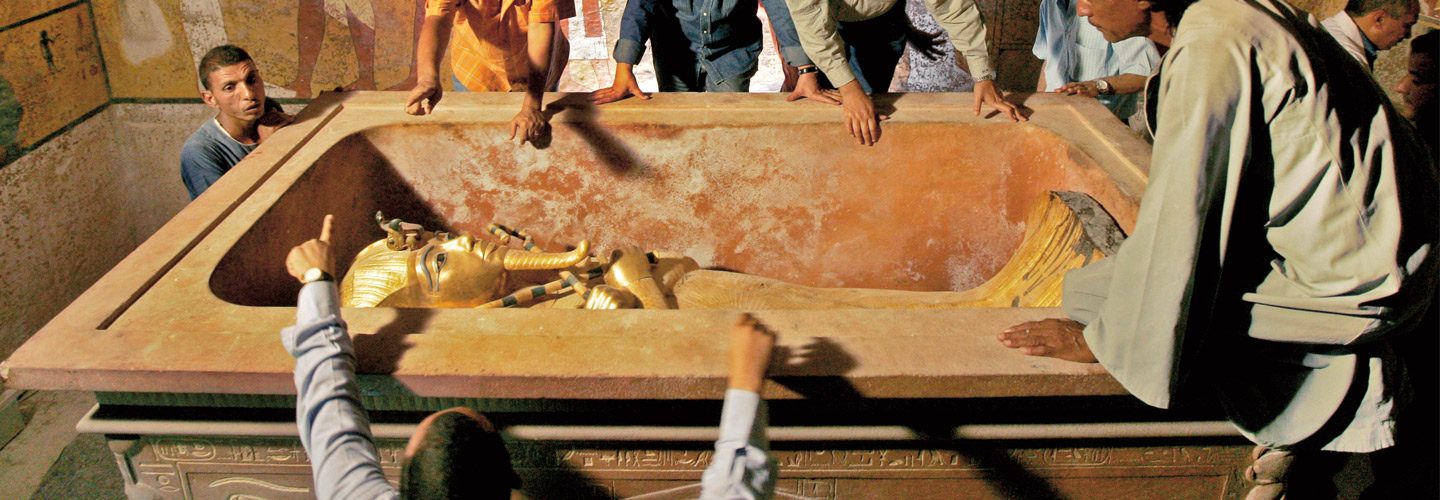

British archaeologist Nicholas Reeves proposed the theory last year after studying new laser scans of Tut’s burial chamber—one of four rooms in the 3,300-year-old tomb, which is located in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. On two walls, Reeves noticed faint lines and other clues that could indicate doors to two other rooms. One of them, he says, may lead to the burial chamber of Nefertiti, who is thought to be Tut’s stepmother. It might even be that the tomb itself was originally the queen’s.

Though tantalizing, Reeves’s theory has its doubters. This past spring, a conference on Tutankhamen in Cairo, Egypt’s capital, turned into a debate over the idea that Nefertiti could be buried with him.

The fact that this tomb has become the source of such controversy nearly a century after its discovery reflects the world’s fascination with ancient Egypt—and, in particular, with Tut and Nefertiti.

For more than a year, technicians equipped with lasers and radar scanners have been exploring Egypt’s most famous tomb. They’re on a mission to unravel a mystery: Did the mummy of Tutankhamen (too-tong-KAH-mun), also known as King Tut, have company in his tomb?

A leading archaeologist thinks so. He believes the mummy of Queen Nefertiti lies hidden behind one wall of Tut’s tomb. Queen Nefertiti is another legendary figure.

The possibility has shaken the world of Egyptology. “It could be the discovery of the century,” said Mamdouh el-Damaty. He is a former government official in charge of guarding Egypt’s antiquities. Such a find could also provide a much-needed tourism boost to the country. (Egypt has been affected by political instability in recent years.)

British archaeologist Nicholas Reeves proposed the theory last year after studying new laser scans of Tut’s burial chamber. The burial chamber is one of four rooms in the 3,300-year-old tomb. The tomb is located in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. On two walls, Reeves noticed faint lines and other clues that could indicate doors to two other rooms. One of them may lead to the burial chamber of Nefertiti, he says. Nefertiti is thought to be Tut’s stepmother. It might even be that the tomb itself was originally the queen’s.

Though exciting, Reeves’s theory has its doubters. In spring 2016, there was a conference on King Tut in Cairo. That is Egypt’s capital. The conference turned into a debate over the idea that Nefertiti could have been buried with Tut.

The tomb has become the source of great controversy nearly a century after its discovery. This reflects the world’s fascination with ancient Egypt—and, in particular, with Tut and Nefertiti.