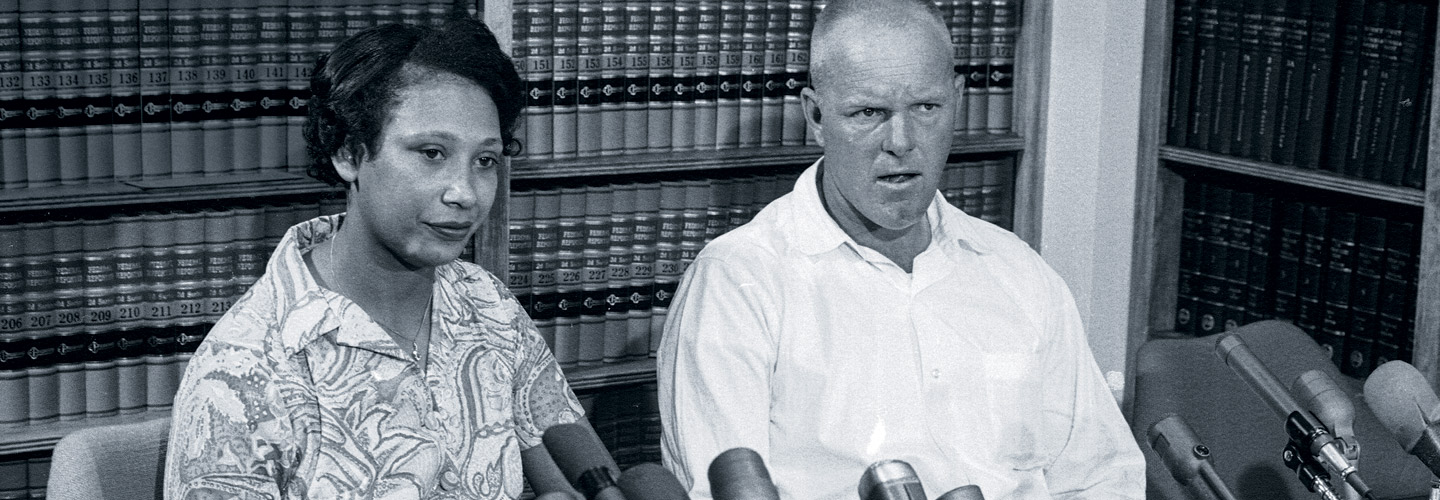

The sheriff and his men came about 2 a.m. Richard Loving heard the knocking, but before he could get out of bed, the officers broke through the door and burst into the bedroom. Later, Mildred Loving recalled the sudden panic, the flashlights in her face.

“They asked Richard who [I was]. I said, ‘I’m his wife.’ The sheriff said, ‘Not around here you’re not.’”

The place was rural Caroline County, Virginia, in July 1958. Richard, who was white, and Mildred, who was black and Native American, had committed a crime. They had violated Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, which made it “unlawful for any white person in this State to marry [anyone except] a white person.”

For their offense, the Lovings were nearly imprisoned, then banished from Virginia. But they fought back in court. In the end, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor, erasing 16 state laws that banned interracial marriage. Nearly 50 years later, Loving v. Virginia continues to help protect the right of Americans to marry anyone they want.

The sheriff and his men came about 2 a.m. Richard Loving heard the knocking. Before he could get out of bed, the officers broke through the door and burst into the bedroom. Later, Mildred Loving recalled the sudden panic. She remembered the flashlights in her face. “They asked Richard who [I was]. I said, ‘I’m his wife.’ The sheriff said, ‘Not around here you’re not.’”

It was July 1958. The place was rural Caroline County, Virginia. Richard was white. Mildred was black and Native American. They had committed a crime by violating Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The law made it “unlawful for any white person in this State to marry [anyone except] a white person.”

For their offense, the Lovings were nearly imprisoned. But they fought back in court. In the end, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor. This ruling erased 16 state laws that banned interracial marriage. Nearly 50 years later, Loving v. Virginia continues to help protect the right of Americans to marry anyone they want.